Every individual is equal before and under the law and has the right to the equal protection and equal benefit of the law without discrimination and, in particular, without discrimination based on race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, sex, age or mental or physical disability.

"So the deal, according to my Dad, was that if all the Chinese guys in Vancouver volunteered for this service, we would get the right to vote and citizenship."

"I'm very proud to be Chinese and I'm proud to be Canadian. Everybody says, 'Oh, what's your first country of choice?' It’s Canada. I know where I came from, but Canada is my country."

"I suppose we're the bridge between Canadians and the new immigrants and we can see things from both sides. We can better help them assimilate in a way that they can be Chinese and still be Canadian."

"We have the collective responsibility to build a country based firmly on the notion of equality of opportunity, regardless of one’s race or ethnic origin."

Identity & Success

Changes to Canada's legal system and ongoing contributions from its many immigrant communities continue to shape the country and the character of Canadians. Concepts of identity and belonging have been influenced by changes in national values and social attitudes. Multiculturalism as public policy, and based on respect for ethno-racial and cultural diversity, are key to Canada's identity and image today.

As a reflection of how Canadians see themselves, the 2006 census showed a total population of 31,612,897 and recorded more than 200 ethnic origins that respondents used to identify who they are. The census found 1,346,510 people who identified themselves as being of Chinese origin. This is in stark contrast to the 25 ethnic groups identified in the 1901 census, when the Chinese Canadian population was 17,312.

About a third of those surveyed, or 10,066,290, identified their ethnic origin as Canadian. Clearly, for many Canadians, the lines of distinction around ethnicity are starting to blur. In fact more than 40 per cent of Canadians reported multiple ethnic ancestries in the 2006 census.

next page >More Chinese from China, Hong Kong, Taiwan and other countries of the Chinese diaspora have come to Canada since immigration policies changed in the late 1960s. Significantly, the Canadian Government in 1982 adopted the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, guaranteeing equal rights under the law, regardless of "race, national or ethnic origin" among other factors.

Chinese Canadians enjoy equal rights with the rest of the country. The perseverance of the Chinese railroad workers, who consciously chose Canada as their country and then struggled to belong, has benefited the entire country.

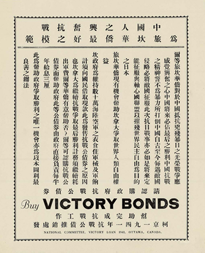

< previous pageWorld War II marked a turning point for the Chinese Canadian community, as Canada matured as a country and social attitudes around exclusion changed. Many Canadians were sympathetic towards China, which was seen as an ally in the Asia-Pacific theatre of war, and to the plight of its people who suffered under the Japanese occupation.

Chinese Canadians had also served their country – Canada – in the war, despite earlier discrimination over their enlistment and participation. Britain had even called upon the Chinese Canadians for special duty in operations behind enemy lines throughout Asia. At home, the Chinese Canadian community in Vancouver raised about $1 million for the war effort in China. A general estimate of the overall contribution of Chinese Canadians to the war effort is about $5 million, or about $125 per capita. Remittances to family and home districts, where possible, enabled relatives in China to survive the war.

Overall, the war effort changed perceptions of Chinese Canadians, both from outside the community, among white Canadians, as well as from within, where the younger generation asserted themselves to claim their rights as citizens.

next page >Important changes to Canadian laws that affected Chinese Canadians' legal identity were made after the war. Lobbying by community, including the war veterans, led to the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1947. The same year, Canada adopted its first Citizenship Act, which combined various laws that helped define citizenship, including the right to vote.

By 1967, immigration law reform had eliminated national origin as a main criterion for Canadian citizenship. Other immigration policy barriers were lifted, allowing Chinese Canadians to reunite with family members living overseas, though in many cases the changes came too late.

< previous pageDespite the odds, and through hard work and perseverance, Chinese have earned the right to be Canadian. The common thread running through railway workers' families is the strong belief that Gold Mountain - Canada - would deliver a better life.

Chinese Canadians accept and celebrate their dual identity – defined by their ethnicity and their nationality. Ties that Bind interviewee Alexandria Sham is proud to be the first Canadian-born person in her family, a century after her grandfather first set foot in this country. Other interviewees have different, often more complex, experiences around identity. Landy Ing-Anderson talks about the complexities of being Chinese Canadian, having a French Canadian grandmother and being part of the First Nations community. Kwoi Gin is still getting comfortable with being Canadian.

Today, Chinese Canadians live everywhere in Canada. Chinatown has changed from being a social refuge - where Chinese could feel safe and enjoy their community – to a cultural one, open and welcoming to all visitors. Both Landy and fellow interviewee Cindy Leong relate their experiences of Chinatown while growing up.

next page >Chinese Canadians have also embraced Canada and its cultural traditions. Several Ties That Bind interviewees relate family stories about their love of the game, evoking scenes of "Hockey Night in Chinatown". Larry Kwong found inspiration for his sports career, listening to the "Voice of Hockey" Foster Hewitt, deliver his play-by-play accounts on the radio, above his family's store in Vernon, B.C. David Chu remembers sharing take-out Chinese food during Saturday night hockey games – and feeling all the more Canadian. Ron Lee still wonders how his grandmother became a diehard fan of the Toronto Maple Leafs.

Through the generations, Chinese Canadians have had to reconnect with one another and with the broader community in their search for identity and belonging. And Canada has had to come to terms with its own history to accept Chinese as Canadians.

< previous pageToday, as in the past, Canada looks to immigrants for its future prosperity. Contemporary values around multiculturalism and respect for diversity have the potential to create a more inclusive society. As Canada has evolved, so has the Chinese Canadian community.

As long-time immigrants, the Chinese railroad workers and their descendants have laid the foundation for newer generations of immigrants to be successful in Canada. Being Canadian still requires newcomers to choose Canada and to have the courage to commit their lives to this country in the hope that their perseverance will be rewarded.

For the Chinese Canadians, success can be measured in the ways they have struggled to belong and contributed to Canada's history. There have been many milestones, including: Kew Dock Yip, Gretta Wong Grant and Margaret Gee, who were among the first Chinese Canadians to become lawyers; Vancouver's Douglas Jung, a World War II veteran, becoming the first Chinese Canadian Member of Parliament in 1957; Vivienne Poy being appointed as the first Chinese Canadian Senator in 1998, and Hong Kong-born Canadian journalist Adrienne Clarkson serving as Governor General from 1999 to 2005.

next page >Chinese Canadians are recognized in the professions. They are community leaders and organizers. They contribute to all aspects of Canadian life. Among Ties That Bind participants, there are engineers, an artist, an architect, a social worker, a journalist, business people, a professional hockey player, filmmakers and a teacher. Today, young Chinese Canadians are unlimited in what they can do.

The Chinese Canadian experience is also being shaped by more recent immigration. Immigrants from China, Hong Kong and Taiwan now are as likely to be bankers, doctors and engineers as they might be students, domestic helpers or unskilled workers. By fulfilling these roles in Canadian society and choosing Canada as their home, they share the right to be called "Canadian."

< previous pageOn June 22, 2006, Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper rose in the House of Commons to deliver an official apology to Chinese Canadians for more than six decades of legislated discrimination against them.

"Mr. Speaker, I rise today to formally turn the page on an unfortunate period in Canada's past. One during which a group of people – who only sought to build a better life – was repeatedly and deliberately singled out for unjust treatment," the Prime Minister intoned, starting a new era for Chinese Canadians with Parliament acknowledging and recognizing their contributions to Canada's history and identity.

"I speak, of course, of the Head Tax that was imposed on Chinese immigrants to this country, as well as the other restrictive measures that followed."

next page >Fulfilling a promise to apologize to Chinese Canadians when his government was elected earlier the same year, Harper spoke of the community's history. He acknowledged the tough decisions made by more than "15,000 of these Chinese pioneers" to leave their families to seek their fortunes in Gold Mountain. These Chinese, mostly teenagers and young men, "became involved in the most important nation-building enterprise in Canadian history – the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway."

"But from the moment that the railway was completed, Canada turned its back on these men," he said. What followed was 62 years of legislated racism against Chinese in Canada. It began with the various federal head taxes on Chinese immigrants, from 1885 to 1923. Outright exclusion of all Chinese followed with amendments to the Chinese Immigration Act, which came into effect on July, 1, 1923. Newfoundland, which did not join Confederation until 1949, had enacted similar discriminatory laws from 1906.

< previous page | next page >"The Government of Canada recognizes the stigma and exclusion experienced by the Chinese a s a result," the Prime Minister said. "We acknowledge the high cost of the Head Tax meant many family members were left behind in China, never to be reunited, or that families lived apart and, in some cases, in extreme poverty, for many years.

"We also recognize that our failure to truly acknowledge these historical injustices has prevented many in the community from seeing themselves as fully Canadian."

The Prime Minister then apologized to Chinese Canadians before the House of Commons, speaking in both English and French, and then breaking parliamentary tradition by also speaking Cantonese and saying, "Gar nar dai, doe heem" - Canada is sorry.

Most Chinese Canadians agree on the importance of the apology. Actual redress for those who directly suffered the consequences of the head tax and the Exclusion Act is still being debated in the community. Ties That Bind interviewee David Wong tells the story on one of his aunts, who had paid the head tax and qualified for $20,000 redress payment, but refused to accept the compensation.

< previous page