"We have seen Canada entering from both oceans upon the great work of the railway ... and from the Pacific...and this has actually been done before British Columbia has been admitted [into confederation] ...Canada has acted in good faith."

"Today British Columbia passes peacefully and ... gracefully into the confederated empire of British North America."

"There appears to be an impression around that we propose to work Chinamen on our Railroad contracts, to the exclusion of white labour ... we shall employ both classes of labour, and shall furnish employment for 3,000 white men ..."

"Mr. [Albert Bowman] Rogers ... surveyor ... has at last found a practicable pass or passes through these formidable obstacles to railway progress..."

"Thanks to your far seeing policy and unwavering support the Canadian Pacific Railway is completed. The last rail was laid this (Saturday) morning at 9.22."

Building the CPR

British Columbia joined confederation in 1871 after Prime Minister John A. Macdonald promised to build a transcontinental railroad that would link the province to the rest of Canada. Work was to start within two years of joining and be completed within ten years. However, politics, finances, mismanagement and scandal delayed the start of construction. Critics said that building a railroad through the Rocky Mountains was too costly and a waste of manpower. Macdonald’s Conservative government fell in 1873 and then came back to power in 1878. As the deadline approached, British Columbia put pressure on the Canadian government to fulfill its promise. Some, like B.C. politician Amor De Cosmos, threatened to withdraw the province from confederation and join the United States.

After a two-month bitter debate in the Canadian House of Commons, the railroad finally received approval on February 15, 1881. The date was also the launch of the Canadian Pacific Railway Company, which was started by a group of businessmen. The government gave the CPR $25 M in cash, 10 million hectares of fertile land, and an exemption from taxes. In exchange, the CPR agreed to complete the railway by 1891. The railroad would be built in two sections. The western section would move east over the Rocky Mountains and join up with the central section, which was to begin in Ontario and move west. The two sections would eventually connect at Craigellachie, B.C.

In 1867, four provinces - Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Quebec and Ontario - formed Canadian confederation. Manitoba joined in 1870. At the time, British Columbia was a crown colony of Great Britain, separated from the rest of Canada by the Rocky Mountains. The colony was under great pressure. The gold rush that began a decade earlier had ended and the region was in an economic depression and in debt. There was also a desire on the part of some people for British Columbia to be annexed to the United States. In 1869, a group of property holders and businessmen wrote The Annexation Petition, which was delivered to American President Ulysses S. Grant. The petition asked the President to begin negotiations with Great Britain for the transfer of British Columbia to the United States.

In 1868, Amor De Cosmos, who became British Columbia's second Premier in 1872, helped to found the Confederation League, an organization that promoted joining Canada. The Confederation League was instrumental in unifying those people who supported confederation. Over the next several years, opinion was divided. In 1870, "The Great Confederation Debate" took place in the B.C. Legislature and the terms for joining confederation were established. The terms included a transcontinental railroad link to the rest of Canada. In Ottawa a few months later, representatives for British Columbia successfully negotiated entry into the Canadian confederation. On July 20, 1871 British Columbia officially became Canada's sixth province.

The enormous job of building the western section of the transcontinental railway fell to 37-year-old Andrew Onderdonk, an American engineer and construction contractor who had just completed the San Francisco sea wall. Onderdonk was the front person for a group of wealthy American financiers. Onderdonk supervised the construction of 341 km (212 mi.) of the main line in British Columbia.

In 1880, the Canadian government awarded Onderdonk four contracts to build four sections of the railroad through the Fraser River Canyon. In 1882, he was awarded a fifth contract for the section that ran from Port Moody on the Pacific coast to Yale, B.C. He agreed to a payment that was below his own estimate for the cost to build the railroad. The shortfall was more than $1.5 M and he had to look for ways to save money.

He decided to hire Chinese workers who were willing to accept less pay and to also provide for their own living and working needs, even though he had promised the Canadian government to first employ surplus white labour from British Columbia and the rest of Canada, then French Canadians, followed by First Nations and, lastly, Chinese. His decision to use Chinese labour was highly controversial. The Chinese were not wanted in British Columbia, and labour unions, in particular, were opposed to the use of Chinese workers who they believed took jobs away by accepting lower wages.

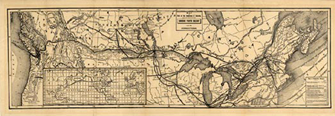

The route for the western section of the transcontinental railroad ran eastward from Port Moody on the coast of British Columbia to Savona's Ferry on Kamloops Lake, in the interior of B.C. It followed the Fraser and Thompson rivers, through canyons, into and out of mountains and across the rivers' many tributaries. The Fraser River, in particular, was the project's vital gateway to the materials and people needed for the railroad's construction. The route continued east to Craigellachie, B.C. where it joined up with the newly built central section of the railroad.

The central section originated in Ontario and followed a route westward that paralleled the Canada - U.S. border. Initially, a more northerly route across the Prairies was proposed, but this route was rejected in favour of the southerly route that took the railway through the newly discovered Roger's Pass even though this route was more difficult and dangerous to navigate. The southern route shortened the distance of the central section by 209 km (130 mi.).

The western section landscape presented major engineering challenges, and bridges, tunnels and retaining walls had to be built. Onderdonk began work on the line north of Yale, B.C. in May 1880. Yale was on the Fraser River, and mountains on either side rose up to 2,438 km (8,000 ft.). The mountains were made of granite, one of the toughest rocks in the world. It took eighteen months of daily, round the clock blasting to bore four major tunnels. More than thirty tunnels were made in the first 27 km (17 mi.) north of Yale, and more than 100 trestles and bridges were built in a 40 km (30 mi.) section.

In a simple ceremony on November 7, 1885, at 9:22 a.m. the western and central sections of the transcontinental railroad were officially joined at Craigellachie, a small hamlet in the Selkirk Mountains of British Columbia. The final rail had been measured and cut earlier in the day. The 7.75 m (25 ft. 5 in.) rail was laid on the ground but left loose to be spiked in place at the ceremony.

CPR director Donald A. Smith was given the honour of driving the iron spike into the railway. Only a small group of people witnessed the event including Major A. B. Rogers, the surveyor who had discovered Rogers Pass, the mountain pass that made a southern railway route across the country possible. A handful of dignitaries from Winnipeg, Montreal and Toronto stood side by side with workmen. The first blow by Smith bent the spike, it was removed and a fresh spike was struck squarely and slid into place. A hushed crowd broke into loud, excited cheers. The moment was recorded in a photograph that has since become a symbol of national unity.

The monetary cost of the railway was about $52 M Canadian (around $1.3 B in 2010) but the human cost cannot be calculated. The famous "Last Spike" photograph tells only one part of the story. The people looking at the camera are white. Not one Chinese man is present. In this final moment, the story of the Chinese railway worker – his labour, sacrifice, and struggles – is omitted from the historical record.