"It is simply a question of alternatives: either you must have this labour or you can't have the railway."

"My Dad came over in 1884 on a clipper ship...he went for the gold mining. He joined the gold rush."

"[Grandfather] Willy Nipp came over in 1881 to work at the railroad, and he worked there from 1881 to 1884. We're not sure where he worked ... but he did come from the county of Yin-Ping in Guangdong Province."

"They came over here from China and they didn't have proper clothing and they weren't aware of the climate. They were running away from starvation ... "

"He [grandfather] was with his [three] cousins. They were only about eight or nine years old ... the three boys came over together with tags around their necks identifying who they were and their birthdates."

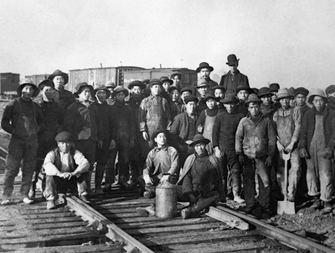

Chinese Railroad

Workers

Chinese labour was used to build the railroad, and later to maintain it. Over 17,000 Chinese came to Canada from 1881 through 1884. Several thousand came from the coastal areas of the United States where they helped build the American transcontinental railroad, but the majority arrived directly from southern China. While most of these arrivals worked as labourers on the railroad, exact numbers are unknown.

They encountered a hostile reception in British Columbia. The province already had a sizeable Chinese population following the gold rush in the late 1850s, and racism towards the Chinese was widespread. Newspaper articles and editorial illustrations of the time repeatedly portrayed the Chinese in a degrading way. Many feared that Chinese workers, who were willing to accept lower wages, would take jobs away from white workers. Also, the Chinese culture was abhorrent to white Canadians who did not understand Chinese cultural practices in areas such as dress, living conditions and even funeral rites.

next page >In the period leading up to building the railroad, during its construction, and afterwards, numerous proposals were put forward to limit or restrict Chinese immigration, Chinese rights, and the participation of the Chinese in the Canadian economy. Though most were defeated some were passed like the 1872 British Columbia Qualifications of Voters Act that denied Chinese and First Nations the right to vote. Later, when they were no longer needed to work on the railroad the Chinese Immigration Act of 1885 was passed, aiming to slow down Chinese immigration by charging a $50 head tax upon arrival in Canada.

< previous page"Gold Mountain" is a name given by Chinese to the north Pacific Coast regions of North America. The name was first used after gold was discovered in California in the late 1840s, and in British Columbia a decade later. Over time, the meaning of "Gold Mountain" expanded beyond acquiring wealth through finding gold, to obtaining prosperity.

The first Chinese to prospect for gold in British Columbia were those men that had worked the California gold fields. When those fields began to dry up, the prospectors moved north to the newly discovered gold deposits along the Thompson River in the Fraser Canyon, arriving by boat at Victoria on Vancouver Island in the spring of 1858. Within a year, other prospectors were arriving directly from China. The Victoria Daily Colonist reported that an estimated 4,000 Chinese arrived in 1860 alone. The gold rush transformed Victoria from a sleepy town of 300 British inhabitants in 1858 to a robust community with 1,577 Chinese residents and 2,884 white residents by the spring of 1860.

Most of the men moved on to the gold fields, but not all the new arrivals prospected for gold. Some like Chang Tsoo from San Francisco became merchants who provided supplies to the fortune seekers. Others found work in coal mines and in the fishing industry, cleaning and canning fish.

The railroad workers were also coming to "Gold Mountain". They hoped to earn enough money to escape the poverty they left behind in China.

Most of the Chinese railway workers came from the two southern coastal provinces of Guangdong and Fujian. They spoke Cantonese, or one of several sub-dialects. Many were peasants. They followed the principles of Confucianism, which placed a great emphasis on respecting elders, honouring the past, and honouring the family, with the goal of creating a harmonious society. The societies were patriarchal, and the eldest male had authority over family members.

An individual's role in the community was determined by his or her family lineage and by the larger kinship group that he or she belonged to. Kinship groups or clans helped members prosper, and the members, in turn, contributed to the wealth of the clan. Passage to Canada was often paid with money collected by family members or village or clan associations. The kinship system helped to take care of wives and children who were left behind in the village, sometimes for decades, until the return of a husband or father.

In Canada, these social values were maintained as men set up village associations in Victoria to assist newcomers. Individuals sent remittance money back to their families and their villages, and often paid for village necessities such as a new bridge.

next page >The railway workers were young, sometimes in their early teens. In 1880, the Inland Sentinel newspaper wrote, "Many of them seem mere boys...a very poor lot for railroad work". Some went back to China to marry while others, for a variety of reasons including travel restrictions imposed by the Canadian government, lived out a bachelor life in Canada.

< previous pageChina was a deeply unsettled country in the mid-1800s. Two terrible wars - the Opium War and the Taiping Rebellion - claimed the lives of tens of millions of people; a growing population struggled to find sufficient farmland to feed itself; imported Western goods destroyed the once robust cottage industry that produced goods such as hand-woven cloth; and natural disasters such as floods created further problems with food production. Social stability declined and pirates and bandits terrorized villages. The result was terrible poverty and starvation.

Almost all of the Chinese who came to Canada were from the rural areas of the Pearl River Delta in Guangdong province. Most rented their small farms from a handful of Chinese who owned almost all of the land. Crippling high rents and taxes consumed the farms' profits, forcing the peasants to borrow money to feed their families. Faced with such dire conditions, many peasants moved away from their farms to Canton, the capital of Guangdong, to look for work. Conditions there were not much better since the competition for jobs was intense. The discovery of gold in California and Australia gave hope to peasants. In just a four-year period, from 1848 to 1852, it is estimated that 25,000 men undertook the arduous journey across the Pacific Ocean to the American and Australian gold fields. In the 1870s and 1880s, railroad construction in Australia, New Zealand, the United States and Canada also attracted tens of thousands of men who worked as contract labourers in the hopes of finding financial security.

The majority of Chinese railroad workers came directly to Canada from southern China. Recruitment companies in Guangdong province advertised job opportunities in Canada and arranged passage on ships. The companies also handled an individual's employment contract, and offered some protection to workers after arrival in Canada. The cost for the service was 21/2% of an individual's wage plus about $40 for the passage fare, which was to be paid once work began. The men came in groups as large as a thousand. In 1882, ten sailing ships chartered by Andrew Onderdonk brought 6,000 men from China to Canada.

The trip from Hong Kong to Victoria on Vancouver Island took several months. The Chinese travelers lived in crowded conditions on the three-masted sailing ships. Henry Cambie, Onderdonk's surveyor, writes, "the men below decks slept in closed hatches with bad ventilation...". Food and water were limited, and some men died before the ships reached their destination. At Victoria they boarded ferries that took them across the Georgia Strait to New Westminster on the mainland of British Columbia. Once there, they transferred to small boats for the journey up the Fraser River to the town of Yale, B.C., the last point that could be traveled to by boat.

The 1885 Royal Commission on Chinese Immigration reported that 15,701 Chinese entered Canada from January 1881 through June 1884. An additional 1,700 arrived in the period from July to October 1884 for a total of over 17,000 during the four years of railroad construction, though not all worked on the railroad.